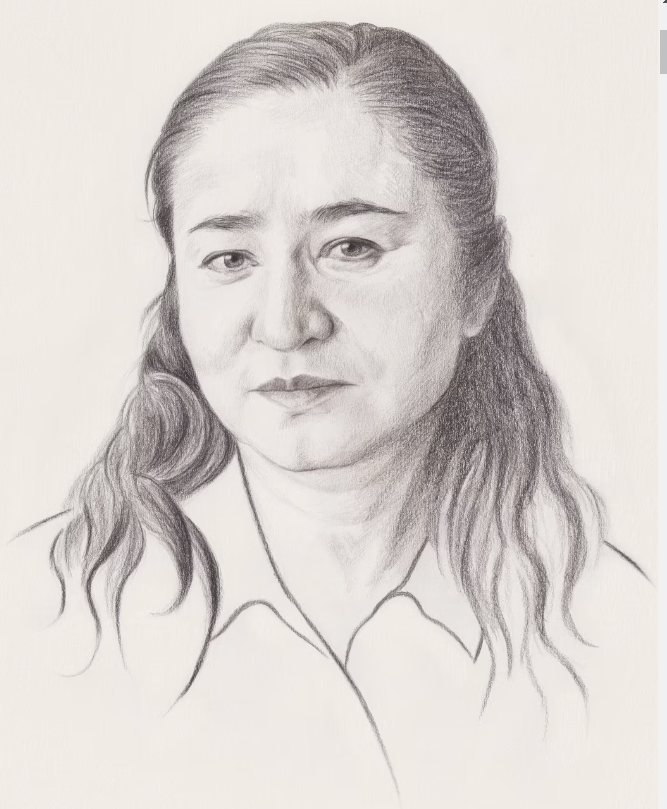

- Pray that Rahile Dawut's life sentence by the current Chinese communist party would be overturned and released from the prison immediately.

- Pray that the current Chinese communist party would stop their unlawful and unjust racist persecutions toward all Uyghurs would stop immediately.

- Pray that God's justice would come upon the current Chinese communist party, and His will be done in all areas of China as it is in heaven.

A car pulls up outside an apartment building in Ürümqi. An elderly woman, in her eighties and frail, emerges and is helped into the vehicle. She is driven to a prison on the outskirts of the western Chinese city.

She is taken inside a room where she is shown, via a screen, her 57-year-old daughter, the Uyghur anthropologist Rahile Dawut. Days later the old woman relays the encounter to her granddaughter, Akeda Paluti. “Your mother is doing well,” she says. “Try not to worry.”

Rahile’s life was devoted to the preservation of cultural diversity across the vast Xinjiang region, nearly three times the size of France and covering about one-sixth of modern China.

For centuries, ancient Silk Roads wove past its mountain ranges, lakes, deserts and valleys. Today, officially called the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, it shares borders with Russia and Mongolia; Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan; and Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Rahile insisted on conducting gruelling fieldwork. She regularly travelled hundreds of kilometres from the capital Ürümqi to isolated villages to research the local Mazar — the shrines and tombs, sometimes attached to mosques, where saints have been buried or where miracles happened — as well as the farmers and craftsmen to understand the traditions etched into their daily lives.

She recorded the oral histories that local leaders had for centuries offered to pilgrims; their poetry, music, folkways and other traditions.

Rahile showing video she shot to young people from the Tajik Youth Cultural Center in Guma, Xinjiang, 2005 © Studio Lisa

Rahile showing video she shot to young people from the Tajik Youth Cultural Center in Guma, Xinjiang, 2005 © Studio Lisa RossBefore Rahile, the few textbooks that included Uyghur oral histories gave scant recognition to where they came from or how they were collected. Rahile traced not only the region’s Muslim traditions but also pre-Islamic traditions of Buddhism and shamanism, finding song lines and rituals connecting the people of Xinjiang to their ancestors across central Asia and beyond.

These myriad threads, she knew, were at risk of being lost for ever amid the encroachment of modernity and the steady creep of cultural homogeneity pursued by the ruling Chinese Communist party.

For years, Rahile worked this way. When she returned to her husband and daughter from weeks on the road, there was never enough room for all the material she had collected.

Boxes of hard drives, discs and video tapes were stuffed under the beds. Sitting at her desk she wrote long into the nights, Uyghur folk music playing in the background, her dark eyes beneath a sweep of thick black hair. Every now and then, she sprang into dance.

This article is the cover story of the FT Weekend Magazine, April 27/28

This article is the cover story of the FT Weekend Magazine, April 27/28Rahile was born in the first years of the Cultural Revolution, a period when religious leaders and places of worship were attacked as enemies of communism. While religious persecution was tempered in China under Mao Zedong’s successor Deng Xiaoping, the intellectual class in Ürümqi, which Rahile and her family were part of, were never seen as particularly devout in their observance of Islam.

Not completely secular, their personal faith was mostly expressed through core moral teachings. She told her daughter it was important to always be honest, to always be grateful for each meal. Later, in private, she said she was uneasy about Pan-Islamic practices — women wearing black veils, people not eating outside — gaining traction in western China during the 2000s. These changes, she told friends, meant local Uyghur societies were losing some of their unique traditional values and becoming less distinguishable from Middle Eastern Islam.

Rahile, whose father was a university professor, read voraciously in her youth and became a star student. After marriage and giving birth to Akeda, her parents encouraged her to pursue graduate studies in Beijing while they helped look after the little girl.

In the late 1990s, Rahile became the first Uyghur woman to gain a doctorate in folklore studies from Beijing Normal University.

One of Akeda’s earliest memories, at five or six, is of travelling with her parents by train for days for her mother’s graduation ceremony, a journey of nearly 3,000km east.

They cycled around the Chinese capital, her mother pointing out some words on signs in English, encouraging her young daughter to memorise them. She was strict, but only by example. When they returned to Ürümqi the celebrations continued, and Akeda’s uncles and aunts gently teased the young girl about how hard she would need to study if she was to replicate mother’s success.

Rahile with her daughter Akeda at Nanshan, near Urumqi, c.2000. Akeda now works as a data analyst in Seattle © Akeda Dawut

Rahile with her daughter Akeda at Nanshan, near Urumqi, c.2000. Akeda now works as a data analyst in Seattle © Akeda DawutRahile’s research was considered groundbreaking by her peers and, increasingly, her methods were emulated by younger Uyghurs and visiting foreign researchers, who she selected, trained and nurtured.

Preserving the culture and sharing it with the outside world was a meaningful pursuit, binding her students together. When they were not in the field, their time was spent almost entirely in one of two places, Room 604 of the Minorities Folklore Research Center Rahile had founded at Xinjiang University, or in Rahile’s home.

Over dinners at Rahile’s table, she counselled her flock on everything from research methods, study grants, scholarships and job hunting to their love lives. “If you choose my field,” Rahile told her younger students, “you probably won’t be rich. But you’ll be happy.”

There were good years. Rahile’s professional output — books, journal articles, speeches — gained her international recognition. Her lectures drew audiences at Harvard, Cornell, Cambridge.

In August 2008, speaking in her slightly high-pitched, near-perfect English, she gave the closing address at a conference she had helped organise in Ürümqi on Mazar culture across the Silk Road. Earnestly she thanked her “dear students” for their help, the international guests for suffering high airline prices at the time and Xinjiang University’s foreign affairs officials for their support.

As she thanked the event’s sponsor, Japan’s Toyota Foundation, a rogue smile flashed across her lips. “In the future, if I ever have the chance to buy a car, I will make sure it’s a Toyota.”

But everyone knew Rahile was walking a dangerous tightrope. She was considered something of a master at it. Academics in Xinjiang were exquisitely aware of the omnipresence of the Chinese Communist party.

Racism towards the Uyghurs was prevalent. Foreign academics visiting the Xinjiang capital saw how their local friends, esteemed scholars, “couldn’t get a fucking taxi at night”.

And yet, for two decades Rahile worked within the system, balancing the pursuit of research as well as it could possibly be done despite the darkening sensibilities and rising paranoia of the party-state.

She was fastidious. She made sure her students did not engage with banned books, that they obtained consent for recordings, saw that they cut personal opinions and avoided direct criticisms of government policy from their dissertations.

Her greatest gift as an ethnographer, colleagues say, may have been her ability to “meet people where they are at”.

This meant not just putting local, usually poor, worshippers, farmers and craftsmen at ease, but always giving face, due respect, to officials, and seeking the proper permissions for her travels, interviews and recordings.

Rahile recording an elder in Xinjiang, 2005. Her great gift, say colleagues, is her ability to put people at ease © Studio Lisa

Rahile recording an elder in Xinjiang, 2005. Her great gift, say colleagues, is her ability to put people at ease © Studio Lisa RossLike most academics in China, she was a party member, obtained her degrees from state universities and received funding grants from the Ministry of Culture.

When the university ruled that her masters students must submit their dissertations in Chinese — after they had been completed in their native Uyghur — she paid for the work to be translated.

When a foreign academic’s passport was confiscated, Rahile visited the local police station to retrieve it, assuring them the visitor was not an agent from a foreign state.

When students were questioned or detained for possessing recordings of the Koran, Rahile could rescue them, assuring police they were students of religion and did not pose a threat.

Even so, by 2016, there were signs that Rahile’s own mood was darkening. She had long tried to encourage officials to reclassify Xinjiang’s religious traditions and places as part of China’s cultural heritage — something that could be preserved and protected, not forgotten or suppressed.

Increasingly, the project was incompatible with the attitude in Beijing towards Uyghurs and its hardline policies.

That year, after a flight she was on to Hong Kong was diverted through Chengdu, south-western China, local police came to her room in the middle of the night. While she was not apprehended, her harassment outside Xinjiang was another indicator of the spreading culture of persecution towards Uyghurs.

Rahile had often jokingly told her female students to think of the frequent and invasive body searches they encountered travelling in and around Ürümqi as a free massage.

But then Rahile, tired and pushed, surprised one student by saying the searches were becoming too much. She said she wished she hadn’t returned from her last trip abroad.

Another student came to her torn over whether to pursue her studies overseas or stay in Ürümqi to be closer to her family. “Just go,” Rahile told her. “We don’t know what will happen tomorrow.”

Then, in December 2017, Rahile was taken by the Chinese state. For the past six years, close friends and family have been frozen in time, replaying their final conversations with her over and over in their minds.

None realised the imminent crisis she faced. Looking back now, it all seems so obvious.

Since the early days of Mao, Xinjiang has been a headache for the Communist party leadership in Beijing and the ethnically Han Chinese officials dispatched to govern in Ürümqi.

Under Communist party rule there has been a huge flow of Han migration to the region, especially to the northern urban areas. Whereas in 1949, Han Chinese accounted for fewer than 7 per cent of the population, today the region of 25 million people is composed of 45 per cent Turkic Uyghurs, who are mostly Muslims, 40 per cent Han and 7 per cent Kazakhs, with the remainder made up of dozens of other ethnicities, including smaller Muslim groups.

For many years, the Chinese government was reluctant to publicly acknowledge threats posed by small pockets of separatism and religious extremism.

But in the early 2000s, Beijing started to recalibrate its approach to the region, reflecting apprehension after the 9/11 attacks. In 2002, the State Council, China’s cabinet, published a document titled “East Turkistan Terrorist Forces Cannot Get Away with Impunity”, the first comprehensive public allegations of more than 200 incidents in the 1990s, including 31 acts blamed on terrorists.

China soon ramped up co-operation with the US “war on terror” and subsequent international campaigns to eradicate transnational Islamic fundamentalism.

In 2009, after protests against racism by thousands of Uyghurs turned violent and were followed by brutal state reprisals, the government cracked down. Surveillance and limits on Uyghurs’ worship and travel were expanded.

A series of deadly events followed, including an SUV ploughing into tourists in Tiananmen Square in 2013 and a 2014 knife attack at a train station in Kunming, southern China, which killed 29 people and injured about 140.

Chinese security officials and experts started to express concern over the expanding geographic reach of the attacks, their frequency, sophistication and the rising number of casualties.

Ultimately it was Xi Jinping, who came to power in 2012, who set the country on a course to rewrite the history of Xinjiang.

Two years after taking office, he conducted an inspection tour of the restive region. Just hours after he left, explosives were detonated at Ürümqi’s train station and bystanders were attacked by two men with knives.

Critics say that under China’s most powerful leader since Mao, Beijing not only crystallised its resolve to eradicate the threat of terrorism, but that the party’s high-level policy towards China’s non-Han minority groups shifted from promoting the “unity of the Chinese nationalities” to ensuring the “shared consciousness of the Chinese national community”.

This was a change from a cautious tolerance of diversity to the dogmatic pursuit of a unified Chinese nation, Xi’s new narrative sought to tie contemporary Chinese people, regardless of their true ethnicity, language or cultural background, to 5,000 years of a singular, glorious, Chinese civilisation.

Under the banner of “anti-poverty”, the government built what it said was a network of vocational and technical training centres across Xinjiang. The state said these facilities were to boost the economic prospects of the region’s poorer people while also aiding in its deradicalisation efforts.

Western governments and human rights experts now say that these facilities were internment camps, which, at their peak from about 2017 to 2019, were used to detain hundreds of thousands — possibly more than one million — Uyghurs and other Muslims. They claim many prisoners were subjected to re-education and forced labour.

During the final days of the Trump administration in January 2021, Mike Pompeo, then US secretary of state, said China had “committed genocide” against the Uyghurs and other ethnic and minority groups in Xinjiang.

The phrasing has been reaffirmed under the administration of President Joe Biden. The UN’s top human rights body would later find that Chinese repression of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity”.

For their part, Chinese officials describe “the so-called Xinjiang issue” as a lie used to undermine the nation’s stability and development.

In 2017, just months before she disappeared, a colleague warned Rahile: “You and your students are all so interested in religion. Just be careful, religion is sensitive.”

Rahile responded firmly: “Any religion is sensitive, and it is not about religion. This is about how Uyghur life is intertwined, embedded with religion.”

Despite the crackdown, Rahile’s circumstances seemed, to those around her at least, unchanged. She was a respected academic, working for a major state university, leading state-funded research projects.

But in late November 2017, the head of the university’s humanities department told Rahile she needed to travel with him to Beijing for a research conference. If Rahile felt a sense of acute personal danger, she guarded it closely. In the days leading up to the trip, Rahile and another colleague only discussed what dresses she should pack.

Using WeChat, Rahile also spoke to her daughter Akeda, who had been living and studying in the US for several years.

Their conversation was normal. Akeda, then in her early twenties, updated her mother on the long hours she was spending at the library, upcoming interviews and her failed attempts at cooking for herself.

Rahile was encouraging on all fronts, especially her daughter’s efforts in the kitchen. After the call, she sent a quick voice message. “I need to fly to Beijing now. I will call you when I arrive tonight.”

It is not known whether Rahile ever made it to Beijing or was intercepted and taken by police or security officials in Ürümqi. But when she failed to surface, her inner circle went into a state of panic, searching for any information of her whereabouts.

Soon it seemed likely that Rahile had become a victim of the state’s crackdown on Xinjiang’s intellectual class. Still, they were hopeful that Rahile’s discipline in navigating the system would mean any detention would be shortlived. In early 2018, there were some signs that this was the case.

One of Rahile’s close friends reached out to a contact in Beijing. Communicating cryptically via WeChat, she wrote: “I heard my friend is in hospital?”

The friend replied, “Yeah, I heard that too. But I think it is not very serious. She’s just going to have some health checks and after that they will release her.”

Another rumour circulated that Rahile was being held and investigated in relation to accusations of mishandling of state funding. While potentially serious, the prospect of such allegations gave some people close to her a glimpse of optimism as they knew officials would find no evidence of corruption. But then there was only silence.

Rahile was tried in secret in December 2018 at an intermediate people’s court in Xinjiang. A subsequent appeal was rejected. For much of the next five years, her immediate family and closest supporters were in the dark.

Human rights campaigners lobbied the Chinese government publicly, and Chinese officials privately, for any information. Some of the messages they received back were alarming.

John Kamm, executive director of the Dui Hua Foundation, a small US group working on behalf of at-risk detainees in China, heard from his contact in Beijing at the time: “You have said she is moderate and not political. This, in fact, is a very serious case, what you said is not right.”

Rahile en route to the pilgrimage site of Imam Jafar Sadiq in the Taklamakan desert, Xinjiang, 2005. Her focus, she once told a colleague, was not religion but how Uyghur life is ‘intertwined with religion’ © Studio Lisa Ross

Rahile en route to the pilgrimage site of Imam Jafar Sadiq in the Taklamakan desert, Xinjiang, 2005. Her focus, she once told a colleague, was not religion but how Uyghur life is ‘intertwined with religion’ © Studio Lisa RossMore scraps of information — rumours, really — circulated among her family and friends and the broader exiled Uyghur community. Akeda, still living in the US, held on to the hope that the sentence handed down would not be too long, and that one day she would see her mother again.

And then, early last year, one account emerged which suggested the worst: a lifetime sentence for the crime of “splittism”, endangering state security.

This was confirmed last September by Kamm, who was shown an official document. On Chinese government stationery, signed by a senior Chinese official, was a statement: Rahile Dawut was sentenced to life in prison.

With her network of international connections, Rahile’s name was one among about 450 other academics, intellectuals, writers and musicians who campaign groups believe went missing around the same time. Most remain behind bars.

Rahile’s case, experts say, is now emblematic of the Chinese government’s crackdown on the Uyghur people moving from the re-education phase to long-term imprisonment.

According to Uyghur Human Rights Project, a US-based rights group, official statistics show more than 578,000 criminal convictions in Xinjiang during the six years from 2017 to 2022. The figure does not include the unknown numbers of people in the region’s internment camps and other forms of arbitrary detention.

If accurate, that would indicate an imprisonment rate for Uyghur adults in Xinjiang of about 5,800 per 100,000, more than one in every 17 people. That would mean non-Han people in Xinjiang are imprisoned at more than 50 times the rate of Han people, and that non-Han people imprisoned in Xinjiang account for about one-third of China’s entire prison population.

The state’s obliteration of Islamic culture, everything that Rahile had worked to preserve, has also intensified.

An FT analysis of satellite imagery late last year revealed that of the 2,300-plus mosques once featuring Islamic architecture and Arabic features, at least three-quarters have been modified or destroyed since 2018. There are signs Beijing appears increasingly unconcerned with international reputational damage over Xinjiang.

Propaganda efforts to showcase the region as “harmonious” and “wondrous” are again ramping up as officials tout the region’s tourism and investment opportunities.

In response to FT questions, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing said that China is ruled by law and that policies related to Xinjiang have “deep” public support.

The ministry said there have been no terrorist attacks in Xinjiang for seven consecutive years, but that the region still faces threats and challenges from terrorism and extremism and further counterterrorism and deradicalisation work is “very necessary”.

It also said there is “strong momentum” across the region’s economy, consolidation of ethnic unity, harmonious religious development and the protection of the rights of people from all ethnic groups.

“We firmly oppose anyone fabricating lies and rumours, hyping up issues related to Xinjiang, and interfering in China’s internal affairs and judicial sovereignty,” the ministry said. It did not comment on Rahile Dawut specifically.

Six months after finding out about her mother’s fate, Akeda who lives in Seattle working as a data analyst, is still in shock.

She is also intensely angry at the Chinese Communist party and deeply fearful for her mother’s health. But she wants to keep fighting for her release, a decision that means remaining in exile. “I don’t want to see her spend the rest of her life in prison,” she told me.

Akeda has troubling dreams in which she is back home, with the threat of arrest weighing her down. These kinds of dreams are common among the Uyghur diaspora who, like her, spend much of their spare time online, reading news and searching through social media for any information about the fate of their loved ones.

As international attention has been drawn away from Xinjiang by conflicts elsewhere, a sense of despondence has pervaded the Uyghur movement.

When Akeda’s grandmother tells her that her mother is OK, and not to worry, she is not sure what to believe.

She hopes it is true, that Rahile can receive visitors from time to time. But she’s seen no photos, no videos, no letters, no proof. So she hangs on to a memory. The image of her mother, at her desk, writing into the night after a long trip away, springing up suddenly into dance.